The word alegria is commonly translated as “happiness” or “merriment.” As you might imagine, the alegria palo is typically played at an upbeat tempo and in a major key (usually A or E).

While not as formulaic as sevillanap, alegria dance accompaniment does have a set of distinct “song parts” which, in more traditional arrangements, are often assembled in a predictable order. Many of the same principles apply to solo instrumental arrangements as well.

Structure and Compas

The basic structure of alegria por baile (“for dance”) can be schematized like this:

- Intro

- Copla (verse) & Falseta (guitar melody)

- Footwork

- Silencio

- Castellana

- Escobilla

- Buleria

Within this basic schema, sections can be rearranged, doubled, or eliminated altogether.

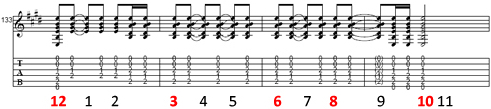

The compas of alegria is based in 12s and, like solea, is accented on the 3, 6, 8, 10, and 12 beats:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

The examples provided in this article (and in the accompanying PDF transcription) are blocked out in 12 beat phrases, starting on 12:

Alegria in E Major

Here are the parts of a traditional alegria in E major and a video example of the piece.

Download the PDF of the full arrangement. The letters next to the section subheadings below correspond to the rehearsal letters in the PDF score.

Introduction

Guitar Intro (A) (0:00)

In this arrangement I’ve chosen to start with a falseta, this one based on the falseta Tomatito plays for Camarón on the Paris 1987 album. You could also play a traditional four compas “marking” progression that moves through the basic alegria chords (as we’ll see an example of this progression later in the footwork rehearsal letter “L”), or begin your alegria with the temple.

Temple (B) (0:16)

The temple is traditionally the cante (singing) intro, usually a melodic string of nonsense syllables, most commonly “Tirititran tran tran.” In this arrangement the temple section is four compases of alegria rhythmic marking with some melodic variations. For an instrumental or accompaniment arrangement, this temple could also serve as an introduction. The first line of the temple provides an example of the basic alegria compas rhythm:

Llamada (C) (0:38)

“Llamada” literally means “call” and it is the signal to the singer, dancer, or guitarist to take the lead. In this case, since there is no cante (singing), the guitarist is “calling” him- or herself. Though this is not always necessary for a choreographed piece, in this example it helps the musicians and dancers keep track of where they are in the arrangement by clearly defining and delimiting the different sections of the alegria. In this arrangement, llamadas also help to keep the different sections from running into each other; they allow the piece “room to breathe.”

First Copla

Copla (D) (0:48)

The copla is the “verse” of the alegria. Even though there is no cante in this particular arrangement, we can still use the copla chord progression to give the alegria some substance and a sense of movement. This gets us away from simply alternating between the E and B7 chords.

This first copla moves through the base alegria chords (E, B7, A) and is played to a traditional alegria rhythm, echoing the rhythm used in the intro falseta. In the second copla we’ll see some rhythmic and chord variations that can be used to make this basic pattern more interesting.

Llamada (E) (1:15)

As discussed in “C” above, the llamada here is more of an articulation from one section to another than a “call” properly speaking. When used as a transition in this way, the llamada still ends on the ten count—and still closes the musical phrase—but it also leads into the next section. More open, legato, rhythm playing (versus abrupt contratiempo) will help to achieve this effect.

Parts “F” through “I” below can be thought of as variations of the copla/llamada structure seen above and can be used to give length and variety to an accompaniment—or eliminated, as you see fit.

Falseta

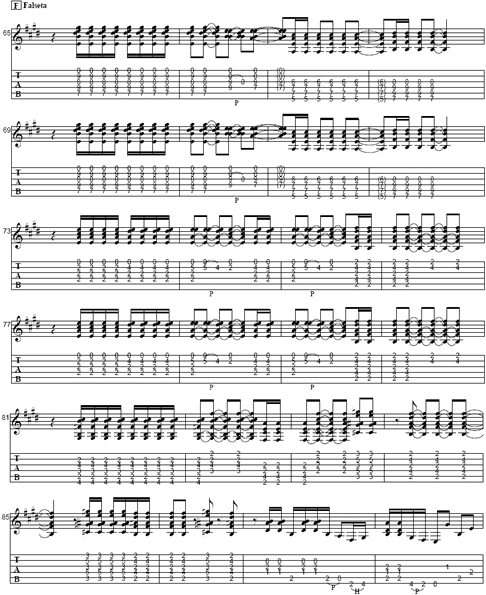

Falseta (F) (1:25)

This falseta is based on a passage Chicuelo plays in “Dulce Sal.” The main part (or theme) of the falseta is four compases long and is followed by a two compas remate. “Remate” comes from the verb “rematar,” “to finish (something).” In this case it’s the tying off or finishing of the falseta.

The opening rhythm of the falseta echos the traditional alegria rhythm we’ve used in the introduction and first copla:

Llamada (G) (1:56)

As above, the llamada here is used to move smoothly between parts of the alegria.

Second Copla

Copla (H) (2:08)

This copla follows the same basic structure as the first copla, but introduces three new elements to give the progression we started with above a whole different feel.

Syncopation

Instead of accenting the 12, 3, 6, 8, and 10 beats, here we can play around those beats in order to. When syncopation is done well, it highlights the underlying compas and in a way provides a new “point of view” on it. In order to pull this off, however, you must, as a guitarist, always know where the compas is—and where you are in it. You should be able to tap out the compas with your foot while playing a syncopated passage.

Alternate Chord Positions

The first and second compáses of this copla are both hanging out on the E major chord, but the chords are played in different positions, which gives them a different feel. During the first compas, the open position E major is played, but only on the three highest strings. For the second compas, the E moves up to the seventh fret, here played in the “C form” (i.e. the form you would use if you were playing an open C major chord). You can also play the E major in an “A form” at the seventh fret—or in the “D form” at the ninth fret, or the “G form” at the twelfth (which is, however, pretty hard to grab!). By moving your chord positions around, you not only get different “sounding” chords, but you’re also presented with different ways to ornament them by grabbing the notes that the various forms put in reach.

Passing Chords

When moving from the second to the third compas in this copla, we “pass” through a C#7 (beat 3, bar 103) and an F#m7 (bars 104 and 105) in order to get to the B7. E major to B7 is still the base progression, but the passing chords give that simple movement more “color.” Passing chords are typically (though not always) the “seven” chord one string lower (an inverted fourth) than the chord at which you eventually want to arrive.

When to use passing chords—and how long to stay on them—is largely a matter of taste. Too many passing chords and the underlying chord structure starts to get lost; not enough and you find yourself repeating the same three chords over and over. Experiment to find out what works best for your particular style.

Llamada (I) (2:30)

Again, we’ll use the llamada to move smoothly between parts of the alegria.

Footwork

Subida (J) (2:40)

“Subir” means literally “to rise” or “to wind up.” In the subida, the dancer will build his or her footwork both in intensity and in tempo. For the guitarist, the subida generally starts at or slightly below the main tempo of the piece and begins relatively softly. As it progresses, it gets faster and louder.

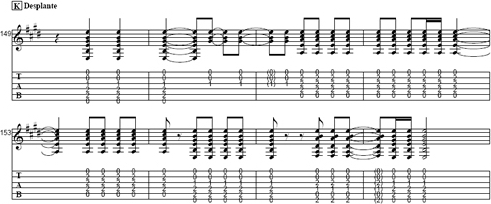

Desplante (K) (3:07)

The desplante marks a break in the dance, generally at the high point or climax (though not necessarily the end) of a footwork section. The dancer will signal the desplante by raising his or her arms and taking a step or two backwards.

While the standard alegria chords and compas will work with the desplante, a more dramatic (and traditional) accompaniment is given here. These chords pass through the A, breaking up the regular chord sequence, and accent the 7, 9, and 11 (i.e. play in contratiempo) during the first compas. The chords and compas resolve as the dancer finishes his or her desplante, and the toque (guitar playing) returns to the base compas.

Footwork (L) (3:16)

Here the toque marks four compases of the basic alegria progression while the dancer performs his or her footwork. As with much of alegria this section can be stretched or compressed depending on what your dancer has in store. As mentioned above (“A”), this progression could also be used to introduce your alegria.

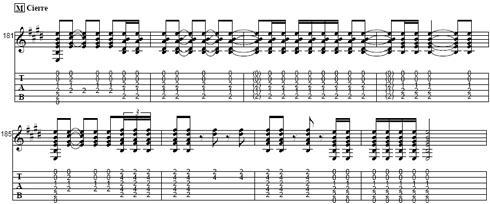

Cierre (M) (3:46)

The cierre is the close of a section of song or dance. The cierre shown here has more of a “modern” feel. The first compas plays like a llamada, but the second compas is more heavily syncopated and moves to the E major sooner, closing definitively on the ten count. (We’ll see a more traditional cierre following the castellana at rehearsal letter “R”.)

Silencio

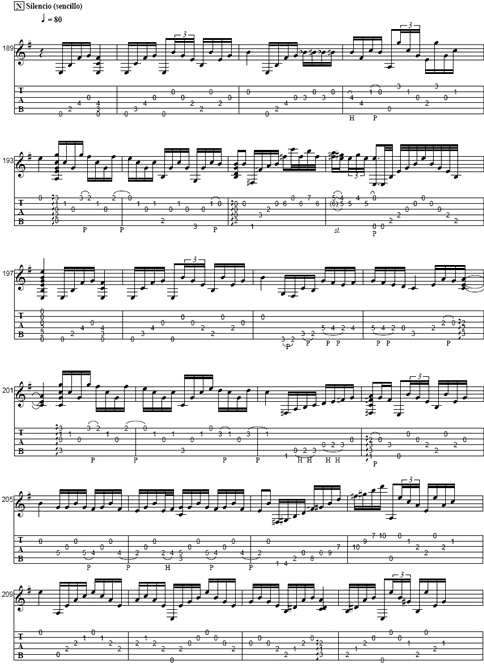

Silencio (sencillo) (N) (3:50)

Sencillo means “simple” and refers to the most common form of silencio which spans six compases. Silencio, of course, translates as “silence,” though rest assured—we’re not talking about total silence here, but rather the silence of the singer. In fact, the silencio is typically a place where the spotlight (so to speak) is on the toque.

The silencio sencillo is traditionally played much slower than the rest of the alegria and in a minor key, as is transcribed here. The silencio I’ve arranged for this score is adapted from the Grupo de José Galván alegria and, again, has a more “modern” feel:

Many traditional silencios resolve after six compases, upon which the guitarist moves on to the next section in his or her alegria. The traditional silencio can, however, be extended another four compases by the doble.

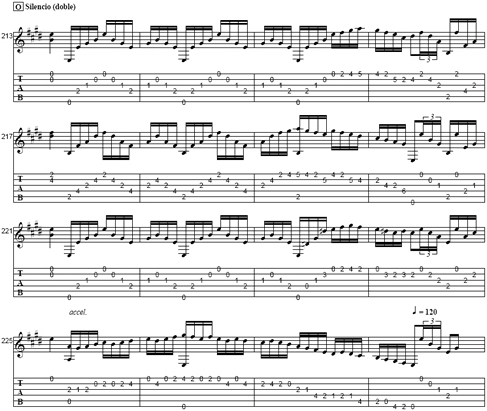

Silencio (doble) (O) (4:47)

The doble is less common than the silencio sencillo, but is a good way to add more texture and variety to your alegria. The doble I’ve transcribed here is mostly arpeggio, but it can easily include more picado passages or chord variations. The traditional doble is four compases long and is played in the same major key as the rest of the alegria.

Notice that the last compas of the doble accelerates in order to bring the tempo back up to alegria speed by the end of the silencio. Another alternative is to use the next section (a llamada, for example) to pick up the pace.

Castellana

Llamada (P) (5:20)

As above, the llamada here is used to move smoothly between parts of the alegria.

Paseo Castellana (Q) (5:25)

The castellana links the silencio to the escobilla and ends with a cierre. As you’ll notice in the score, the guitar part for the castellana is not much different than the standard alegria toque, such as you would play for footwork. What sets the castellana off from other sections is primarily the cante (singing) and the baile (the way it is danced).

Cierre (R) (5:42)

The cierre given here is of the more traditional variety. I’ve placed this cierre here because the castellana is a more “traditional” element of alegria, though this cierre and the cierre above (cf. rehearsal letter “M”) are interchangeable.

Escobilla

Escobilla (S) (5:50)

Escobilla literally means “brush,” or “small broom.” The section takes its name from the brushing/shuffling step dancers use at times during the escobilla. This section, like the subida, often begins slowly and accelerates as the footwork builds.

While escobilla toque, like much of the alegria, is open to interpretation, the arpeggiated forms of E major and B7 are the most common accompaniment. Even given this minor constraint, however, the escobilla still offers lots of room for interpretation and embellishment. Each escobilla phrase is typically two compases long:

Following this initial phrase are four examples of different ways the escobilla can be played, all of which might be played in turn in any given section of footwork. An escobilla section may be much longer than is written here. Likewise, sections of escobilla may be punctuated by llamadas or interspersed in other sections.

Llamada (or Ida) (T) (6:46)

In the example given here, the escobilla is tied off with a llamada before this arrangement transitions into buleria. In very old styles of alegria, this is where the ida would go.

Buleria

Buleria de Cadíz (U) (6:55)

Like many flamenco forms, the alegria often ends by shifting to a “lighter” song form, in this case buleria de Cadíz. Buleria de Cadíz is, of course, played to the same compas as any other buleria, but the chords are in the key of E major. As you transition to buleria you will want to both increase your tempo and change the aire of your playing. Even though you’re still moving (with passing chords) between E major and B7, whereas in alegria the chord change typically happens on count ten of the compas, in buleria the chords change on the twelve count.

Cierre (or desplante) (V) (7:25) The final cierre transcribed here is another more “modern” innovation to alegria. One could also make the final close with a desplante or either cierre shown above.

Interpretation and Solo Guitar

Though traditionally performed in this order, a good alegria accompaniment may contain all or only a few of these elements, either in this order or in some other order that makes better sense to the dancers and musicians involved. It is art after all. The important part, of course, is that there is some sense to the arrangement, that it builds meaningfully in some way, and that musicians and dancers are able to use the form to “say something.”

Basically, the goal is to get away from simply playing notes or falsetas and instead play the form. This is why learning how to accompany other flamencos is important to learning to play solo flamenco guitar. Flamenco is by nature an ensemble art form. An accomplished flamenco guitar player will be able to evoke flamenco cante and baile, even when there are no singers or dancers present. This intuition—–along with staying in compas, of course—–is a key element in the difference between playing nice music inspired by flamenco and actually playing flamenco.

Next Steps

Once you have the basic compas and form of alegria down, the next step is to add variety and diversity to your repertoire by adding falsetas and varying your style. I recommend practicing with a flamenco metronome both as you learn the basiscs and as you explore new territory. This will keep you in compas and help you understand how new song parts really work within the form.

To take the next step in complexity in dance accompaniment, check out the Solea Accompaniment article, where we’ll explore structuring and playing the solea form for dancers. Solea is considered by many to be the “mother of all flamenco forms.” Although it is much less structured than simpler forms, like sevillana or alegria, solea is also made up of particular forms and structures which, once understood, offer unique opportunities for creativity and individual expression.